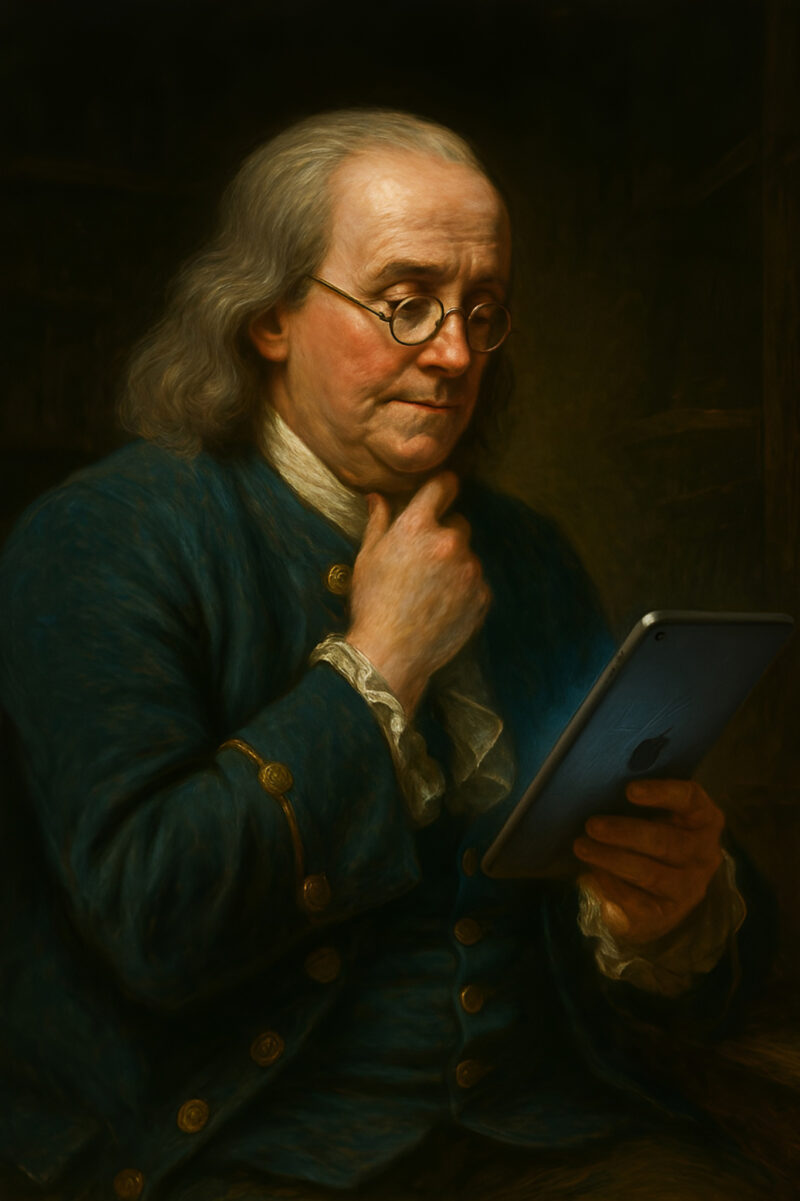

(Or: Why Franklin Would Have Hated Pivot Culture)

Benjamin Franklin spent seventeen years perfecting the lightning rod.

Not seventeen weeks of sprints. Not seventeen months of learning in public. Seventeen years of observation, experiment, and deliberate refinement. He flew his kite in 1752, but he had been studying electricity since 1746 — testing materials, recording failures, refining hypotheses in near obscurity.

This was not the work of a man chasing quarterly metrics.

Franklin was a polymath of uncommon range — printer, postmaster, diplomat, inventor — yet none of his breakthroughs were accidents of restlessness. He did not pivot from publishing to atmospheric electricity because Poor Richard’s Almanack had failed to scale. His mind changed direction as nature does: gradually, with reason, in response to curiosity rather than investor impatience.

He built bifocals because his own eyes demanded them.

He designed the Franklin stove because Pennsylvania winters were cold and chimneys wasteful.

He raised lightning rods because buildings were burning and he understood why.

He followed problems, not market signals.

Today we worship innovation the way past centuries worshipped gold. We canonize disruption as though novelty were self-justifying. We gather in accelerators and co-working spaces, surrounded by whiteboards filled with frameworks for faster failure, leaner hypotheses, more aggressive pivots.

We have built an entire economic theology around the belief that speed of iteration is the highest virtue.

Franklin, ever the pragmatist, would have asked a quieter, more uncomfortable question:

What problem are you truly solving — and have you understood it long enough to solve it well?

This essay is about the difference between two pursuits we have learned to confuse: invention and innovation.

One creates what did not exist. The other recombines what does.

Both are valuable. Both require skill. But they are not the same discipline — and treating them as interchangeable has consequences we are only beginning to understand.

Invention as Discovery

To invent, in Franklin’s sense, was to reveal what was already true about the world. The kite did not create electricity; it proved its presence. Invention begins with wonder, proceeds through observation, and culminates in utility. It is patient, empirical, and disciplined curiosity made tangible.

Invention is the creation of something genuinely new — a solution to a problem that had no prior answer.

The printing press did not improve the scribe; it replaced him.

The transistor did not refine the vacuum tube; it reimagined computation itself.

The polio vaccine did not iterate on the iron lung; it rendered it obsolete.

These did not enhance what existed. They conjured what hadn’t.

Invention says: “Let me understand the principle.”

Innovation, by contrast, is the artful recombination of what already exists — the rearrangement of known parts into new patterns.

It is Uber applying GPS and digital payments to taxi dispatch.

It is Airbnb grafting marketplace dynamics onto hospitality.

It is DoorDash mapping logistics algorithms to restaurant delivery.

Valuable? Absolutely. Transformative, even.

But not invention.

Innovation says: “Let me ship the product.”

One begins in nature’s workshop; the other in a conference room.

One asks “Why does this happen?” — the other, “How quickly can we scale?”

One follows curiosity into the unknown; the other follows capital into the proven-but-improvable.

Both matter. Both demand creativity, rigor, and courage.

But they are not the same discipline — and mistaking one for the other is how progress begins to circle back on itself.

The Pivot as Panic (and Virtue Signal)

Modern startup culture has canonized the pivot — the swift redirection of a company’s strategy when the market rejects its first idea. It’s celebrated as agility, institutionalized as wisdom, and packaged as virtue.

“Fail fast,” we say. “Ship and iterate.” “Fall in love with the problem, not the solution.”

These are fine maxims for innovation, where feedback loops guide refinement in familiar terrain. But for invention, they are poison.

A pivot, in theory, is graceful adaptation. In practice, it is too often a public confession of impatience — a way to disguise the fear of stillness as strategic brilliance.

Franklin would have found it absurd. To discard one’s pursuit at the first resistance is not agility; it is panic dressed as pragmatism. He could not have “pivoted” from electricity after six months of inconclusive experiments. The Wright brothers could not have A/B tested their way to flight. Marie Curie could not have “sunset” radioactivity because early investors grew restless.

Invention requires endurance bordering on stubbornness — the willingness to labor in obscurity long after applause would have faded. It demands fidelity to the problem before the solution is visible, and conviction before validation.

Franklin once wrote, “Energy and persistence conquer all things.” He might add today: “Except quarterly impatience and the tyranny of the dashboard.”

The pivot, when reflexive, is not evolution — it is escape. It’s what happens when we mistake motion for progress, or when fear of being wrong outweighs the discipline of becoming right.

Innovation thrives on iteration. Invention survives on conviction.

And when conviction is replaced by convenience, we don’t accelerate discovery — we abandon it.

The Forgotten Virtue of Refinement

Franklin did not pivot away from the lightning rod when early critics called it blasphemy — an arrogant meddling in divine affairs. He refined its geometry. He clarified its principle. He documented its results. He let evidence do the persuading.

His work was iterative, yes — but iteration in service of truth, not flight from difficulty.

He believed progress was moral before it was mechanical, and that understanding must precede utility.

If Franklin walked into a modern technology company, he would recognize the language of experimentation. He would appreciate the bias toward action. He might even admire the collaborative intensity — the conviction that speed and collective effort can conquer uncertainty.

But he would also sense an absence: fidelity to first principles.

He would see teams pivoting quarterly — not because they had exhausted an idea, but because they had exhausted patience. He would find dashboards measuring everything except understanding. He would hear founders describe themselves as “operators” and “executors” — titles of process, not of discovery.

He would watch organizations celebrate velocity as though motion were progress, and optimization as though refining the wrong thing were nobler than pursuing the right one.

And then, quietly, he would return to his workshop — where problems worth solving are measured not in quarters but in decades, and where the only dashboard that matters asks a single question: Does it work, and why?

The Innovation Debt

Technical debt is well understood: shortcuts taken today that compound into costly repairs tomorrow.

But there exists a parallel burden we have yet to name: innovation debt.

Innovation debt accrues when an organization becomes so proficient at iteration that it forgets how to invent — when it grows masterful at recombining what is known but loses the nerve to create what is not.

You see it in enterprises that can ship features weekly yet haven’t produced a truly novel capability in years.

In teams that optimize acquisition funnels with mathematical precision but can no longer articulate what makes their technology defensible.

In cultures that hire for growth and execution but not for discovery or deep research.

You see it in organizations that measure everything quantifiable and nothing that matters — tracking velocity, conversion, engagement — but not whether they are building anything the world will remember.

Innovation debt feels like momentum. Dashboards glow green. Velocity is high. Revenue climbs.

Until one day, a patient competitor, a zealous startup, or a distant adjacent industry unveils something genuinely new — and the entire optimization machine is rendered suddenly, irreversibly obsolete.Then the bill comes due.

And it cannot be paid in sprints.

The Patience Paradox

Here is what makes this difficult:

Markets reward innovation immediately.

They reward invention eventually — if at all.

The company that iterates fastest on a proven concept captures market share today.

The company attempting to invent a new category may capture it in five years, or ten, or never — contingent on whether the invention works, whether timing aligns, whether capital endures, and whether the team survives the long solitude between insight and adoption.

Rationally, why would any founder choose invention?

Yet someone must.

Because without invention, innovation becomes a closed loop — ever more intricate arrangements of increasingly interchangeable parts.

And so we get seventeen food delivery platforms, each marginally faster at logistics.

Forty-three project management tools, each with trivial workflow variations.

A thousand AI applications, none advancing the underlying science.

This is not progress. It is noise — polished, monetized, and mistaken for momentum. And noise, no matter how optimized, never compounds into meaning.

What Invention Actually Requires

Franklin’s method was simple in principle, uncompromising in practice.

Observe patiently.

He watched storms for years before theorizing about electricity.

He studied the behavior of light and heat before conceiving bifocals.

Observation always preceded hypothesis — never the reverse.

Experiment rigorously.

His electrical investigations were systematic, documented, reproducible.

He did not move fast and break things.

He moved deliberately — and understood them.

Share generously.

He published his findings openly and refused patents on principle.

He believed invention was a public good — that progress accelerates when knowledge flows freely, and that hoarding insight is theft from the future.

Build for permanence.

The lightning rod still works.

The Franklin stove still stands as sound engineering.

He designed not for product cycles or planned obsolescence, but for utility that would outlast him.

This was more than a method.

It was a moral discipline.

He understood that the world changes not by pivoting, but by perfecting —

not by chasing what is new, but by completing what is true.

The Reconciliation

This is not a manifesto against innovation.

Speed matters. Markets matter. Feedback matters.

The discipline of iteration has created immense value — and will continue to.

But we have swung so far toward velocity that we risk forgetting how to do the slower, riskier work — the patient, uncertain labor that produces genuinely new capabilities rather than simply refining existing ones.

The solution is not to abandon innovation in favor of invention, but to recognize them as distinct pursuits — each with its own timeframe, metrics, and modes of protection.

For innovation:

Move fast. Measure constantly. Listen to markets. Optimize relentlessly. Pivot when evidence demands it.

For invention:

Move deliberately. Measure sparingly, if at all. Ignore markets until you have something worth showing them. Explore thoroughly. Persist beyond what seems reasonable.

The mature organization practices both simultaneously.

It innovates with one hand — iterating, optimizing, capturing near-term value.

And it invents with the other — researching, exploring, and building foundations that may not bear fruit for years.

Google once did this: Search and Gmail were innovations built atop known ideas.

PageRank and the Transformer architecture were inventions that opened entirely new frontiers.

Apple still does: each iPhone iteration is innovation, refining what customers already understand.

The M-series chip was invention — a decade-long bet that ARM could replace x86 in personal computing.

Both matter. Both demand funding, talent, and executive protection.

But they cannot be managed the same way, measured by the same dashboards, or judged on the same timelines.

When we forget that distinction, we build organizations full of talented people — optimizing their way toward irrelevance.

In Closing

The next time your team gathers to pivot, pause and ask a simpler question:

Are you inventing, or are you innovating?

If you are inventing, proceed with patience.

The work will take longer than you expect, cost more than you budgeted, and demand faith when evidence is scarce.

If you are innovating, move with speed — but do not mistake velocity for vision, or optimization for discovery.

Franklin’s kite experiment is often misremembered as a sudden flash of genius — a lucky strike that proved electricity could be drawn from the sky.

But read his notebooks. The kite was not the beginning; it was the culmination.

It was experiment forty-seven in a years-long investigation — preceded by Leyden jars, by studies of pointed versus rounded conductors, by systematic trials of materials and geometries, by failed hypotheses patiently refined.

The kite did not reveal electricity. It confirmed what Franklin had already come to understand through long, deliberate observation.

That is the difference between invention and innovation.

Innovation asks: “How can we do this better, faster, cheaper?”

Invention asks: “What if this were possible at all?”

Both questions matter. Both disciplines deserve respect, resources, and room to work.

But only one creates lightning rods.

And only one ensures that, a century from now, something you built will still be standing — not because it was optimal, but because it was true.

Franklin, ever the coiner of useful maxims, might leave us with this:

“Those who pivot without principle shall spin forever.”

— The Adaptive Innovator

October 13, 2025